Her Funeral

There were no crowds to accompany the coffin that left the town house a 10 South Street, Park Lane to be placed in a special train at Waterloo Station, London. The coffin was covered with the dead lady’s white Indian shawl and on it lay a wreath of red lilies from Dr. Shore Nightingale and the family. Among other wreaths was a cushion of flowers: "With the heartfelt regrets of the survivors of the Balaclava Light Brigade, to our benefactress and friend of nearly sixty years.”

There were no crowds to accompany the coffin that left the town house a 10 South Street, Park Lane to be placed in a special train at Waterloo Station, London. The coffin was covered with the dead lady’s white Indian shawl and on it lay a wreath of red lilies from Dr. Shore Nightingale and the family. Among other wreaths was a cushion of flowers: "With the heartfelt regrets of the survivors of the Balaclava Light Brigade, to our benefactress and friend of nearly sixty years.”Three thousand tickets had been issued by the War Office for the memorial service at St. Paul’s Cathedral. Seven hundred nurses from all parts of the country attended, and the old veterans from the Chelsea Hospital, many of whom had fought in the Crimea. The King and Queen and the Queen-Mother and other members of the Royal Family were represented, and also the War Office and Army Council, the Corporation of London, the Prime Minister, Lord Morley, Earl Crewe and Mr. Haldane of the London Times newspaper. E. Cook writes: The offer of burial in Westminster Abbey was declined by her relatives. She had left directions that her funeral should be of the simplest possible kind, and that her body should be accompanied to the grave by not more than two persons. She was buried beside her father and mother in the churchyard of East Willow, near her old home in Hampshire. The body was borne to the grave by six of her "children" of the British Army-sergeants drawn from the several regiments of the Guards. Her desire that only two persons should follow the coffin could not be fulfilled. The funeral arrangements were kept as private as was possible; but there was a wreath of flowers from people of every kind, age and degree, and the lane and churchyard were filled with a great crowd of men, women, and children, most of them poorly dressed.So in keeping with her wishes the coffin, on Saturday, August 27, at a quarter past one o’clock, in a special funeral train from Waterloo Station in London, pulled into the small station of Romsey, in Hampshire, near the New Forrest, where the Nighingale’s family residence of Wembley Park was. The station was almost deserted when the train arrived. The inhabitants of this area to respect the wishes of Miss Florence Nightingale’s executors did not gather to witness the arrival of the great nurse. The funeral procession itself was designed to attract as little public attention as possible. The hearse was a glass -paneled car, which showed the coffin covered with a white cashmere shawl, often worn by Miss Nightingale, and decorated with a number of beautiful wreaths. At the foot of the coffin rested the floral tribute sent by Queen Alexandra. It was a cross of mauve orchids fringed with white roses and lilies. Attached to it was a black-bordered card containing the following inscription in the handwriting of her Majesty: To Miss Florence Nightingale.  On the lid of the coffin also were a large chaplet of crimson sword lilies and a wreath of heather, both sent by the members of the Nightingale family. Following the hearse were five coaches containing the chief mourners.

Behind the coffin came the pathetic-looking company of mourners, and in the rear walked Miss Nighingale’s commissioner, who was always to be seen by callers at her house in South Street. Preceding the coffin from the church to the tomb were six grey-headed old tenants and employes during the lifetime of Miss Nightingale. The wreaths at the graveside numbered some three hundred. On the lid of the coffin also were a large chaplet of crimson sword lilies and a wreath of heather, both sent by the members of the Nightingale family. Following the hearse were five coaches containing the chief mourners.

Behind the coffin came the pathetic-looking company of mourners, and in the rear walked Miss Nighingale’s commissioner, who was always to be seen by callers at her house in South Street. Preceding the coffin from the church to the tomb were six grey-headed old tenants and employes during the lifetime of Miss Nightingale. The wreaths at the graveside numbered some three hundred.

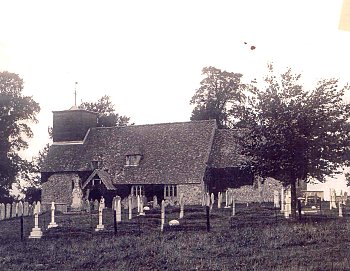

“The Lady with the Lamp” was laid to rest on Saturday in the God’s acre surrounding the parish church of East Wellow, the little Hampshire village where she stayed with her parents in her girlhood. As the little church had accommodation for fewer than 200 people mourners and representative of the gentry and the farming and laboring classes of the district. But room was naturally found for a number of nurses in uniform who came from Salisbury. It was the ordinary burial service, interspersed with some of the favorite hymns of Miss Nightingale simply rendered by the village choir. The opening hymn was “The Son of God goes forth to war.”

The son of God goes forth to war,The 90th Psalm was recited. This was followed by the hymn, “On the resurrection morning,” and finally “Now the laborers task is o’er” was sung. Then the coffin, upon which lay a white cross of roses, liilies, and orchids, which the touching inscription in the Queen-Mother’s handwriting, was carried by a bearer-party of Grenadiers, Coldstreams, and Scots Guards. And seated in the ivy-clad porch waiting to witness the arrival of the cortege was a medalled Crimean veteran, now eighty-two years of age. Who had been three months in hospital at Scutari and who still remembers gratefully the midnight rounds of “The Lady with the Lamp” when the soldiers kissed her shadow upon the wall as she passed by.

Standing at its head was a large cross of white flowers, mounted on a pedestal, from which depended a long satin ribbon bearing the inscription in gold letters, “With grateful appreciation of a noble example. From the matrons and nursing staffs of all the London hospitals.” On one side of it was a chaplet from the Army Council, inscribed “In Memoriam.” On the other side was a floral model of a military lantern, sent by the Army and Navy male nurses “in token of deep gratitude to the pioneer of nursing.” Close by was a cushion of white blossoms with the initial letter “B” formed in blue flowers. “With the heartfelt regrets” said the inscription “of the survivors of the Balaclava Light Brigade Charge. To our benefactress and friend of nearly 60 years.” The committal service was very brief. The drizzle continued while those last rites were performed and the coffin was lowered into the vault. On of the most touching tributes was that sent by Stella Forster, aged seven years, who with a wreath of heather, had sent the following message: “To dear, Miss Nightingale, Please may my wreath be put with the other flowers. I picked the heather and made it myself.” The International Council of Nurses sent a wreath composed of roses, attached to which was the following: “With homage to the honored memory of the foundress of modern trained nursing.” The photos are from the scrapbook of Edward W. Bok.

|

|

Home |